Stone Bridge Press

P. O. Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707

tel 510-524-8732 • sbp@stonebridge.com • www.stonebridge.com

This publication has received the William F. Sibley Memorial Subvention Award for Japanese Translation from the University of Chicago Center for East Asian Studies Committee on Japanese Studies.

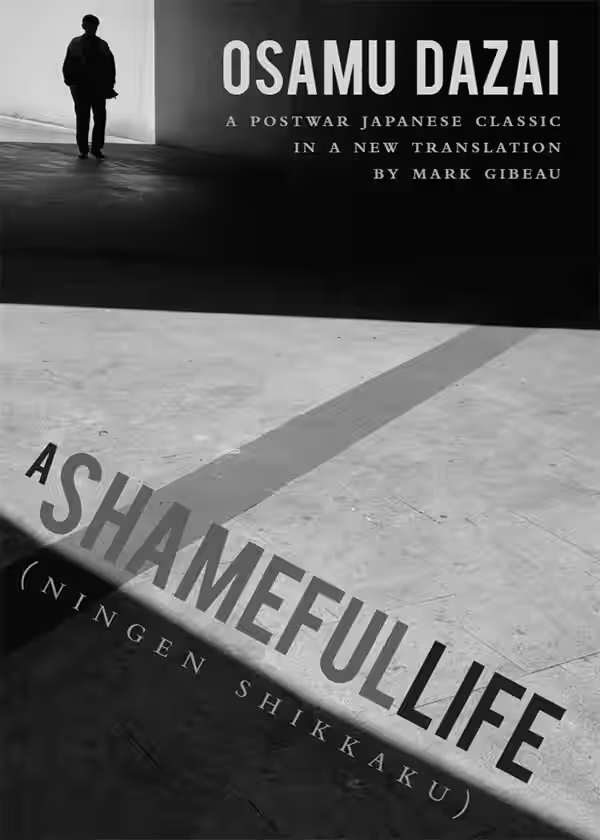

English translation © 2018 Mark Gibeau.

Originally published in Japanese as Ningen shikkaku in 1948.

Except on the cover and title page, Japanese names in this book appear as family-name first.

Cover design by Linda Ronan incorporating a photograph © Andrés Cañal Cañal. Text design by Peter Goodman.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 2022 2021 2020 2019 2018

p-ISBN: 978-1-61172-044-0

e-ISBN: 978-1-61172-932-0

I’ve seen three pictures of him.

The first is a photo of what I suppose might be called his childhood days and appears to have been taken when he was about ten years old. He stands at the edge of a garden pond, surrounded on all sides by a crowd of girls (his sisters and cousins, I imagine), dressed in rough-spun, striped hakama trousers, head tilted thirty degrees to the left and with a hideous grin on his face. Hideous? I suppose that the less perceptive (those with no training in aesthetics) might blandly say, “My, what a cute boy.”

Empty praise perhaps, but the child’s grinning face does possess a hint of what the vulgar call “cuteness,” or at least enough of it to save the remark from crude flattery. Yet anyone with the least experience in aesthetic matters would but glance at the photo before thrusting it away in disgust as though it were a repulsive, hairy caterpillar, muttering, “What an odious child!”

Truly, the more I gaze at the boy’s grinning face the more an inexplicable, disturbing sense of unease grows in me. Look there—it’s not a smile. There isn’t a trace of a smile on his face. The proof is in his hands, balled into tight fists. People don’t smile with hands clenched in fists. It’s a monkey. A monkey’s grin. The face has simply been twisted into an ugly mass of wrinkles. The expression is so strange, so oddly deformed that I cannot help but recoil in revulsion. I’m tempted to call the figure “Wrinkle Boy.” Never in my life have I seen a child with such a peculiar expression.

The second photo also reveals a face that has undergone a surprising transformation. He is a student now. It isn’t clear if the picture is from high school or university, but either way he is a startlingly beautiful youth. Yet, oddly, this photo also lacks the feel of a living, breathing person. Dressed in his school uniform, a handkerchief peeking from his breast pocket, he is relaxed, legs crossed as he leans back in a rattan chair, and, here too, he is smiling. This time it is not the grin of a wrinkled monkey but a finely crafted smile. Still, somehow, it differs from the smile of a human being. It lacks something. The quiet sobriety of life, perhaps, or the weight of blood. It lacks substance, possessing instead the lightness not of a bird, but of a feather. He is but a blank sheet of paper, smiling. From top to bottom everything feels contrived. This is not mere affectation—that falls far short of the mark. Nor is it just frivolity, flamboyance, or an attempt to appear charming. Clearly, he is not simply trying to appear fashionable. Yet, as I look at the photo more closely I experience a vague disquiet, as if I were reading a ghost story. Never in my life have I seen such a peculiar, beautiful young man.

The last photo is the most disturbing. I cannot guess his age. His hair is streaked here and there with gray. He sits in the corner of a filthy room (behind him the wall crumbles in three places), warming his hands over a small charcoal brazier. This time he is not smiling. His face is empty of all expression. It is as though he were already dead, even as he sits there with hands held over the brazier. An ominous, inauspicious photo. And that is not the only disturbing element of the picture. He sits so close to the camera that I can make out each element of his face in detail. He possesses an unremarkable brow, with unremarkable wrinkles. Unremarkable eyebrows, unremarkable eyes, unremarkable nose and chin. I give an exasperated sigh. His face isn’t simply absent of expression, it fails to leave any impression at all. Nothing stands out. I gaze at the picture and then close my eyes. It’s gone. I can see the walls and the small charcoal brazier but the face—the “protagonist” of the room—has vanished like mist in the sunlight, and, try though I might, I cannot bring it back. It is an unpaintable face, impossible even to caricature. Then, I open my eyes. I don’t even feel the fleeting joy of recognition. There is no, “Ah, that’s what he looked like!” To be perfectly blunt, I cannot remember what he looks like even as I stare at the photo with eyes wide open. There is only disgust, irritation, and the almost overpowering impulse to look away.

Even the face of someone slipping into death holds some kind of expression, leaves some kind of mark. But this, maybe this is what it would be like if the head of a carthorse were sewn onto a human body. In any case, a vague sense of revulsion shivers up my spine. Never in my life have I seen a man with such a peculiar face.

I have lived a shameful life.

I can’t understand how this thing called “human life” is supposed to work. I was born out in the country, in northeast Japan, so I was already fairly old by the time I saw my first steam engine. Back then I didn’t realize that the bridges in the station were there simply to let people cross the tracks and get to their platform. I thought they were there to give the station an air of sophistication and fun—like a playground. I maintained this belief for quite some time, and clambering up and down those stairs always seemed to me the height of refined entertainment. Surely, I thought, this was the most considerate of all the services provided by the railroad. When I eventually discovered that they were nothing more than a practical set of stairs, my sense of delight vanished.

Another time, when I was a child, I saw an illustration of a subway. It never occurred to me that it might have been designed with some practical purpose in mind. I thought that people must have grown bored with riding above ground and the underground trains were built to provide new and exciting ways to travel.

I was a sickly child and often confined to my bed. I remember lying there, gazing at the sheets, the pillowcase, the quilt cover and so on, wondering at their insipid designs. It wasn’t until I was nearly twenty years old that I realized that these things actually had a practical purpose, and, yet again, I was grieved by the dismal parsimony of humankind.

I never knew what it felt like to be hungry. No, I don’t mean my family was so wealthy that I never wanted for the necessities in life—nothing so cliché as that. Rather, I mean I had absolutely no idea what the sensation of hunger felt like. I know it sounds strange, but even when I was hungry, I didn’t know I was hungry. Whenever I got home from elementary or middle school, everyone would exclaim that I must be hungry, they remembered what it was like, they were always starving when they got back from school, and would I like some glazed beans? A bit of cake? Sweet buns? They made such a fuss that my inherent need to please others was roused and, muttering something about being hungry, I’d toss a handful of glazed beans into my mouth, but I never had the slightest inkling of what “hunger” was supposed to feel like.

Of course I eat—and I eat a lot—but I have almost no memory of eating out of hunger. I like to eat unusual dishes, delicacies. When I go out, I eat everything put before me, even if I have to force it down. That’s why mealtimes at home were truly the most wretched moments of my childhood.

Ours was an old, country-style house, and at mealtimes the entire household—some ten people—formed two lines facing one another, a small tray set out before each person, and I, being the youngest, naturally sat at the very end of one of those lines in that gloomy dining room. The mere sight of my family, eating their lunch in silence, was enough to send shivers down my spine. Worse still, being a country household, we had the same thing every day. There were no unusual dishes, no delicacies, nor, indeed, any hope of them, so I came to live in terror of mealtimes. Sitting at the very end of that gloomy row of trays, shivering in the cold as I picked up a few grains of rice at a time, shoving them into my mouth, I wondered why people felt compelled to sit down and eat three times a day, every single day. Everyone wore such solemn expressions as they ate that I began to entertain the notion that maybe this was all some kind of ritual. Perhaps, I thought, this was a sort of prayer—this act of gathering in the dreary dining room, all in a row, eyes downcast, three times a day, every day, always at the same time, trays lined up precisely, chewing food in silence whether we wanted it or not. Perhaps it was a ritual to placate the teeming spirits that filled the house.

When people told me I’d die if I didn’t eat I thought they were just making mean threats. Still, that superstition (even now I can’t help but think of it as such) filled me with dread. People die if they don’t eat, so they work. They have to eat. Nothing seemed more impenetrable, incomprehensible, or menacing to me than this.

It seems that I will end my days having never understood anything at all about the lives of human beings. I fear my idea of happiness is completely at odds with everyone else’s idea of happiness. This fear consumes me, sometimes making me twist and turn at night, groaning in agony, driving me to the brink of madness. Am I happy? Ever since I was a small child people have been telling me how fortunate I am, but, for my part, I felt like I was in hell, and the ones saying I was fortunate seemed incomparably and immeasurably happier than I was.

I was so miserable I sometimes thought I’d been afflicted with a dozen curses, any single one of which could crush the life out of a normal person.

In the end, I just don’t understand. I cannot understand the kind or degree of suffering that other people experience. Perhaps their “practical” suffering, the kind relieved by eating, is in fact the most extreme form of suffering—perhaps it is a suffering so ghastly, like the tortures of the deepest circles of hell, that my “dozen curses” pale to insignificance beside it. I don’t know. Yet, if that were the case, how do they endure it? How do they make it through each day without succumbing, without despairing, without committing suicide, even as they go on arguing about politics? Could they be such thoroughgoing egotists, so certain that this is the way things are supposed to be, that they have never once doubted themselves? If so, I suppose it might be easier to bear. I wonder if that is simply the way human beings are and that that is what makes them happy. I just don’t know. . . . I wonder if they sleep soundly at night, if they awake refreshed in the morning. What do they dream about? What are they thinking about when they are walking down the street? Money? Surely that can’t be the only thing. I recall someone saying that people live to eat, but I’ve never heard anyone say that people live for money. Yet, in the right circumstances . . . But, no, I don’t understand that either. . . . The more I think about it, the less I understand and the more I find myself assailed by the terrifying, disquieting idea that I alone am utterly different. I can barely talk to people. I have no idea what to say or how to say it.

That’s when I hit upon the idea of the clown.

It was to be my final attempt at courting humanity. Even though I lived in abject terror of people, I couldn’t abandon them entirely. So I used the single, tenuous thread of the clown to retain my connection. On the surface, a grin never left my face, but on the inside I was locked in a desperate struggle, walking a tightrope, bathed in sweat, the danger of disaster ever imminent as I entertained them.

From the time I was a child I have had no conception of the suffering of others or what was going through their minds as they went about their lives, even among my own family. Terrified and unable to endure the relentless awkwardness of human interaction, I found that, without realizing it, I had transformed into an accomplished clown. Before I knew it, I had become a child incapable of uttering a single word of truth.

When I look at my family photographs from that time, everyone is wearing a somber expression, but I alone—without fail—have my face twisted into a peculiar grin. This is one example of my childish, pathetic clowning.

What’s more, I never talked back when scolded by my parents, not even once. The smallest scolding seemed to me a deafening thunderclap, and it knocked me down with such tremendous force I thought I might go mad. Far from being able to talk back, such scoldings were like the pronouncement of some profound “Truth,” echoing down the generations and across endless ages. Since I lacked the strength to embody that Truth, even at that age, I had already begun to suspect I might be incapable of living among humans. I was incapable of arguing with others, nor could I stand up for myself. If someone criticized me, my first thought was that the other person must be right, utterly and entirely, I must have made a terrible mistake, it couldn’t be clearer. I endured such attacks in meek silence, but on the inside I writhed in agony, near mad with terror.

Of course, nobody likes being criticized and yelled at, but, in my case, I thought I glimpsed a terrifying animal nature in those angry faces—far more frightening and dreadful than any lion, crocodile, or dragon. Though usually concealed, a fit of rage might suddenly tear away the veil, just as a cow dozing idly in a pasture suddenly cracks its tail, obliterating a horsefly with a single blow. My hair stood on end and a shiver ran down my spine when I thought that possessing this instinct might be a necessary condition for living among humans. I came close to despair.

I lived in quivering terror of people, and, since I had no confidence whatsoever in my ability to speak or behave like a human being, I gathered up all of my fears and anxieties and concealed them in a box, deep inside my breast. I took enormous pains to conceal my melancholy and nervousness, and devoted myself instead to cultivating an air of innocent good cheer. Thus, little by little, I was transformed into an eccentric clown.

I would do anything so long as it made people laugh, it didn’t matter what. If I could make them laugh, I reasoned, they might not care that I didn’t really fit into their “lives.” Above all else, I had to avoid sticking out. I had to avoid becoming an eyesore to those human beings. I am nothing, I am the wind, the sky. Such were my thoughts as I strove to entertain my family with my clowning. I played the clown—desperately— even for the maids and servants, as they seemed to me far more incomprehensible and terrifying than my own family.

Once, at the height of summer, I put a red woolen sweater on under my cotton robe and marched up and down the hallway, making everyone in the house laugh. Even my eldest brother, dour and rarely seen to smile, burst out laughing and, as though he found the sight too delightful for words, called out to me saying, “Really, Yō-chan, I don’t think that suits you.”

What’s that? I may have played the eccentric but I wasn’t such a fool that I couldn’t tell hot from cold and I certainly wasn’t going to walk around in a wool sweater. I’d taken my sister’s woolen leggings and, pulling them onto my arms, let the ends peek out from my sleeves to make it look like I was wearing a sweater.

My father was often away on business and kept a villa in the Sakuragi district of Ueno, in Tokyo, where he spent the greater part of each month. Whenever he came home he always brought a mountain of presents for the whole family, even bringing some for our distant relatives. I suppose it was a sort of hobby for him.

Once, before leaving for Tokyo, he gathered all of the children in the parlor and, smiling, asked each of us what we wanted, writing the answers down in his notebook. It was rare for him to be so intimate and friendly with us.

“And you, Yōzō?”

With that, I was struck dumb.

The moment I was asked what I wanted I ceased to want anything at all. What difference did it make? It’s not as though anything could make me happy. At the same time, I was incapable of saying no to anything offered me, no matter how little I might desire it. I could not refuse anything, even if I didn’t like it. If I were being offered something I actually did want I could reach for it only timidly, like a thief fearing discovery, a bitter taste in my mouth as I writhed with indescribable terror. I lacked even the ability to choose one thing over another. I suppose that this failing was one of the causes of what was later to become my “life of shame.”

I just stood there, squirming silently as Father grew irritated. “A book, I suppose? Or there’s a place in Asakusa that sells lion masks, just like the ones in the New Year’s lion dance—just the size for a child. Would you like one of them?”

The moment he asked, it was all over. I couldn’t even come up with a silly response. My clowning had utterly failed me.

“You’d like a book, wouldn’t you?” My eldest brother said, his expression ever serious.

“I see,” Father said, exasperated. He closed the notebook with a loud snap, not bothering to write anything down.

What a disaster! I’ve made Father angry, his revenge will be terrible, I must do something right away, make amends before it’s too late! Such were my thoughts as I lay trembling in bed that night. I slipped from under my blankets and snuck down to the parlor, where I slid open the drawer containing Father’s notebook. Riffling through the pages until I found the list of presents, I licked the tip of a pencil and wrote “LION MASK” before sneaking back to bed. I didn’t want the mask at all. On the contrary, I’d have preferred a book. But I knew that Father wanted to get me the mask and the whole purpose of this late-night adventure—this sneaking into the parlor and so on—was to ingratiate myself with him and to restore his good mood.

In the end, just as I expected, my extreme measures met with resounding success. When Father got back from Tokyo I heard his booming voice from my room, telling Mother all about it.

“So, I’m at the shop and I open my notebook, and there it was—see, right here! ‘LION MASK.’ Not my handwriting, either. ‘What’s this?’ I think. I stood there trying to puzzle it out when it hit me. It’s one of Yōzō’s pranks! He just grinned and stood there like a lump but he must’ve wanted the mask so badly he couldn’t help himself. He’s an odd one, all right. Pretends he can’t decide but then, there it is in black and white. If he wanted it so much all he had to do was say so. I burst out laughing right there in the shop! Call him down right away.”

Another time I gathered all the maids and servants into our Western-style room and had one of the servants pound away on the piano (we may have been out in the country but we possessed all the accoutrements of a respectable household) as I ran around in circles, whooping in an Indian dance and making everyone laugh. One of my older brothers got his camera out and took a photograph of me. When the photo was developed you could see my tiny weenie peeking out from between the folds of the loincloth (I’d worn a thin, calico cloth typically used for wrapping packages) and this only served to bring the whole household down in gales of laughter yet again. I suppose that this too qualifies as one of my surprising successes.

In addition to the dozen or so monthly boy’s magazines I subscribed to, I ordered various books from Tokyo that I read on my own. So I knew all the stories of “Professor Nonsense” and “Dr. Whatsit” and so on by heart. I also knew all sorts of ghost stories, transcriptions of famous storytellers, scary stories from old Edo, and more, all of which meant I was never lacking in material. I kept my family laughing by saying the most outrageous things with a perfectly straight face.

But oh, at school!

I was on the verge of being respected at school. The idea of being respected utterly terrified me. To me, “being respected” meant fooling everyone with a near-perfect deception until someone, some omniscient, omnipotent person saw right through me, crushing my façade into a handful of dust and condemning me to a shame worse than death. That was my definition of “respect.” Even if I managed to deceive people and gain their “respect” eventually someone would find out and others would soon learn the truth. How terrible would their anger and revenge be once they realized they’d been duped? The mere thought of it made my hair stand on end.

I was in danger of being respected less because I came from a wealthy family than because I was, as they say, “brainy.” I was a sickly child, so it wasn’t unusual for me to miss a month or two of school at a time, confined to my bed. Once I missed nearly an entire year of classes. Yet, when the year came to an end I’d ride to school in a rickshaw and take my exams where, still weak from my illness, I’d score at the top of my class. Even when I wasn’t sick I never studied and spent all my time in class drawing cartoons. I showed them to my classmates during recess, narrating as I went and making everyone roar with laughter. When we had to write compositions I always wrote funny stories, even when the teachers told me not to. I knew they secretly looked forward to them. One day I handed in a story, written in a tragic vein, about how I took a train to Tokyo with Mother and, mistaking the spittoon in the corridor for a chamber pot, peed in it by mistake. (I knew it was a spittoon all along. I only did it to make a show of my “childlike innocence.”) Certain it would make the teacher laugh, I snuck out of the classroom as soon as he left and followed at a distance as he walked down the hallway. As soon as he was outside of the classroom he pulled my composition out from among my classmates’ and, reading as he walked, began to chuckle. He stepped into the teachers’ office and, no doubt having reached the end of the story, burst out laughing, tears streaming from his eyes. I saw him pass the story around to the other teachers. I could not have been more satisfied with the result.

A scamp.

I’d succeeded in presenting myself as a scamp. I had successfully avoided being respected. When grades came out I got ten out of ten in everything except “behavior,” in which I received sixes or sevens. This too was a source of no small amusement at home.

My true nature, however, was very nearly the antithesis of a scamp. Young though I was, I had already been violated and exposed to the most desolate things by our maids and servants. To this day I maintain that performing such acts, on a small child, is the vilest, the crudest, and the cruelest crime that one human being can perpetrate on another. Yet I endured it. Sometimes I even laughed, weakly, thinking that in this I had discovered yet another of those “special qualities” peculiar to human beings. Had I been in the habit of telling the truth I might’ve gone to Mother or Father, without shame, telling them of these crimes and begging for their help. Yet even my own mother and father were incomprehensible to me. Appealing to human beings for help? The idea was laughable. Even had I appealed to Father, to Mother, to a policeman, to the government—wouldn’t those people, adept as they were at getting their own way, just make up some story or other and that would be the end of the matter?

I knew all too well that I would never get a fair hearing. In the end, there was no use in appealing to others for help. All I could do, I thought, was to keep silent, to endure, and to persist with my clowning.

What’s that you say? That I have no faith in people? Since when did I convert to Christianity? When did I start believing that all people are sinners? Perhaps some people will scorn me thus. But why should a lack of faith in humans lead you straight down the path to religion? Even the people who mock me, don’t they live their lives happily, with never a thought for Jehovah or any deity, despite distrusting, and being distrusted by, everyone around them? This was also when I was very young, but one time a famous person from my father’s political party came to town to give a speech and a group of servants took me to see it. The hall was packed and I saw a number of people who were particularly close to my father, all clapping with great enthusiasm. When it ended and the audience dispersed, each group made its own way home on the dark, snowy streets, and I heard them savagely criticizing the speech. Some of these voices belonged to Father’s close friends. These so-called “allies” muttered angrily as they complained about Father’s terrible introduction, that they hadn’t been able to make heads nor tails of the speech. Then these very same people later came by our house and, stepping into our parlor, enthused over how successful the speech had been, their faces seemingly suffused with joy. Even the servants were guilty of this. When Mother asked them about the speech, they said it was fascinating. This, after spending the whole walk home complaining that there was nothing in the world so tedious as a speech.

This is but one example and an insignificant one at that. People spend their entire lives deceiving and lying to one another, yet, odder still, nobody seems especially offended by it. Human life is so full of pure, vivid, merry duplicity that I begin to think they don’t even realize they are deceiving one another. For my part, I’m not particularly troubled by the deceptions. After all, what is my clowning but a lie I tell the whole day through? Questions of morality and the notions of right and wrong you find in ethics textbooks have never interested me. What I find incomprehensible are the people who can lead such pure, vivid, merry lives even as they lie to one another. Where do they get the confidence? Nobody has shared this secret with me. Had they done so perhaps I wouldn’t have had to live in such terror of people, or to seek so desperately to please them. Perhaps I would’ve been able to avoid being excluded from the lives of human beings, perhaps I would’ve been able to live my life without tasting the hell of my nightly torments. In the end, it wasn’t because of my distrust of others or because of Christianity that I was unable to seek help even when the servants inflicted their hateful crimes upon me. It was because human beings had sealed their hard shell of trust against me, against this “I” known as Yōzō. Even Mother and Father sometimes did things that were incomprehensible to me.

It seems to me that women have an instinctive ability to sniff out the scent of my isolation, my inability to appeal to others. That, I think, is one of the factors that led to me being taken advantage of at various times in later years.

To women, I was a man who could be trusted with the secret of their love.

A score or more of towering, black-barked cherry trees lined the shore, so close to the water that the waves seemed to lap at their roots. At the start of the new school year their blossoms burst forth, a dazzling pink against the blue of the sea and the rust brown of sticky, newly sprouted leaves. The countless blossoms scattered in a blizzard of petals to form a heaving tapestry atop the surface of the sea, pulled away with each wave only to come crashing back to shore again. Despite neglecting my studies I had somehow managed to gain admittance to a middle school in Japan’s northeast, and this petal-strewn beach was part of its grounds. The figure of these flowers blossomed on the badge of our school caps and even on each button of our uniforms.

One of the reasons Father chose this school of sea and cherry blossoms for me is that distant relations lived all but next door to it. I was left in their care. I was a lazy student in general and, living so close to the school, I always waited until the last minute before rushing off at the sound of the morning assembly bell. Even so, thanks to my clowning I grew more and more popular among my classmates with each passing day.

This was my first experience of living in an “unfamiliar land,” and I decided that life in a foreign place was far easier than in one’s own hometown. This might be put down to the fact that my clowning had by then become second nature and didn’t require nearly so much effort. But I think it was due more to the gap in difficulty between performing for one’s parents versus complete strangers, between one’s hometown and a foreign place. Surely even the most gifted actors, even Jesus Christ the Son of God, was sensitive to that difference. Don’t they say that the actor’s most difficult stage is his hometown? Wouldn’t even the most famous actor hesitate when confronted with a room filled with parents, siblings, wife, and children? Still, I managed it. What’s more, my performances met with considerable success. Surely someone as cunning as I need not fear even the most unlikely of missteps in such a distant town.

My terror of people hadn’t receded in the slightest—it may have even grown—and though fear still writhed deep in my breast I became so adept in my performances that I was forever making my classmates laugh. Even my homeroom teacher, who often complained about how much better the class would be if only I weren’t in it, had to hide his grins behind his hand. I could even make the military drill instructor, with his barbaric shouting and voice like a thunderclap, collapse in laughter with the greatest of ease.

Just when I began to think I had finally managed to conceal my true nature entirely—just as I heaved a sigh of relief—to my utter astonishment I felt a knife pierce me from behind. The one doing the stabbing was, as you might expect, the scrawniest boy in the class. He had a pale, bloated face and wore baggy, hand-me-down robes that must have come from his father or an elder brother. The absurdly long sleeves made him look like Prince Shōtoku from an ancient scroll painting. He got terrible grades in all his classes and always sat on the sidelines during P.E. or military drill practice, and we naturally thought he was a bit simple. It never occurred to me that I should be on my guard even around him.

It was during P.E. and Takeichi (I can’t remember his surname but I think his given name was something like Takeichi) was sitting on the sidelines as usual while we practiced the high bar. When it was my turn I deliberately arranged my face in a determined expression. I gave a great shout as I leapt but, instead of jumping up to grab the bar, I went straight ahead in a long jump, crashing down on my bottom with a thump in the sandpit. It was a completely planned failure. As I had intended, everyone burst out laughing, and I climbed to my feet, brushing the sand away with a sheepish grin. It was then that I felt a poke in my back and saw that it was Takeichi, suddenly standing behind me.

“Show off,” he muttered.

I shuddered. That Takeichi, of all people, should see through me, see that my blundering was all an act—it was all too unexpected. For a moment I felt as though the whole world had turned red, that I burned in the crimson fires of hell. It was only with the greatest of effort that I managed to suppress the mad shriek welling up inside me.

The days that followed were filled with anxiety and terror.

On the surface, I continued to play the hapless clown, making everyone around me laugh, but from time to time a heavy sigh would escape as I realized that, no matter what I did, Takeichi had seen through me, and everything turned to ash. Certain that he would expose me to everyone who would listen, an oily sweat broke out across my brow and I glared about me, eyes rolling wildly with the vacant gaze of a madman. If I could have managed it, I would’ve spent every moment at Takeichi’s side—watching him twenty-four hours a day to make sure he didn’t let my secret slip. I would spare nothing to convince him that it was not an act, that my clowning was real. I wanted to become his dearest friend if I could. Should that fail, I thought, I would have no choice but to pray for his death. Yet, amid all of this, it never once occurred to me to actually try to kill him. Throughout my life I have wished more times than I can remember that someone might kill me, but I have never considered killing somebody else. Doing so, I thought, might only grant those terrifying people a measure of happiness.

In my quest to tame Takeichi I put on a “benevolent” grin, not unlike the smile of a fake Christian, and, head tilted to the left, I gently clasped his thin shoulder, inviting him to come to my house to play, my voice soothing, honeyed. He merely looked back at me in vacant silence. But then one day, near the start of summer I think, a sudden downpour turned the air white with rain just as classes ended, and everyone was milling about near the exit, wondering what to do. I lived just next door so the rain didn’t bother me, and, just as I was about to make a run for it, I noticed Takeichi standing disconsolately in the shadows by the shoe locker. Come on, I’ll lend you my umbrella, I grabbed his hand even as he flinched from me, pulling him out into the rain and running to my house. After asking my aunt to dry our jackets, I succeeded in getting Takeichi to visit my room on the second floor.

There were only three other people in the house. My aunt in her fifties, her elder daughter, about thirty, wearing glasses, tall and sickly looking (apparently she’d been married once but had since returned home. I followed the others’ example and called her Sis) and, lastly, the younger daughter called “Setchan,” who had only just graduated from a women’s college and who, unlike her sister, was short and round-faced. They ran a small shop on the first floor that sold stationery, balls, and bats and the like, but most of their money came from the rent on the five or six row houses that my aunt’s late husband had left them.

“My ears hurt,” Takeichi said, standing in the middle of my room. “They got wet and now they hurt.”

Looking more closely, I saw that both of his ears were in a terrible state. They were so full of pus they looked ready to overflow at any moment.

“Oh, how terrible!” I cried in exaggerated surprise. “That must really hurt!”

“I’m so sorry I pulled you out into the rain,” I spoke tenderly, in an almost womanly manner, as I made my “gentle” apology. I ran downstairs to fetch alcohol and cotton balls and made Takeichi rest his head on my lap as I carefully cleaned his ears. Not even Takeichi saw the evil intent behind this hypocritical act. He even made an attempt at ignorant flattery as he lay there.

“You know, I bet girls will fall for you.”

Many years later and to my regret, I was to discover that these words were a prediction. A prediction so terrible I doubt even Takeichi was aware of it. The words themselves are silly: to “fall for” someone, to have someone “fall for” you. Crude and absurdly foppish, no matter how ostensibly “austere” one’s surroundings, their mere utterance is enough to cause the walls of even the most depressing temple to collapse before your eyes, leaving you feeling blank and empty. Yet it is a peculiar thing. If we move away from such crude notions as how difficult it is to have girls falling for you and instead, to phrase it in literary terms, consider the anxiety of being loved, then those depressing temple walls remain intact.

When Takeichi proffered this absurd flattery, saying that girls would fall for me, I just smiled and blushed as I cleaned his ears and did not say a word. Yet, in fact, I did have an inkling—if only faintly—that there might be something to what he said. Don’t misunderstand me. I don’t write “there might be something to what he said” in that absurd, self-satisfied, boastful sense that such uncouth expressions as “girls will fall for you” typically evoke. That would be too much, even coming from one of the dissolute young men who appear in rakugo stories. Clearly, I did not think, “there might be something to it” in this kind of ridiculous, smirking manner.

Women were a hundred times more difficult for me to understand than men. There were more women than men in my family and, even among my more distant relatives, there were many girls. There were also the maids who had “violated” me, and it is no exaggeration to say I grew up playing exclusively with girls. Yet, despite that, when I was with women I always behaved as though I were walking on thin ice. They seemed to me almost completely beyond understanding. I stumbled about blindly, sometimes accidentally treading on the tail of the tiger and suffering a terrible mauling as a result. Unlike the beatings I received at the hands of men, however, these wounds did not show. Like a kind of internal bleeding, they attacked me from the inside and in the most unpleasant manner imaginable. Such wounds were long and difficult to heal.

Women clasp me to them only to thrust me away. When others are around they scorn me and treat me cruelly, but the moment we are alone they cling to me. They sleep deeply, like the dead. I sometimes wonder if women live only to sleep. I’d made many observations about women, even when I was young. Though they were of the same species I could not help but think of women as altogether different from men, and, oddly, these enigmatic, mercurial creatures cared for me. To say that they “fell for me” or that they “loved me” would not, in my case, be accurate. It is more apt, I think, to say they “cared for me.”

Women were even more at ease with my clowning than men. When I acted the clown around men, they did not, as you might imagine, cackle away, on and on and on. I knew that taking my performance too far around men would end in failure, so I was always careful to wrap things up at just the right moment. Women, though, do not understand moderation. They drove me on and on, demanding more and more of my clowning, calling for one encore after another until I was utterly exhausted. Women really do laugh a lot. They are capable of gorging themselves on pleasure much more than men.

When I was in middle school both the elder and the younger sister would visit my room on the second floor whenever they had a free moment. Each time I heard them at my door I jumped up in fright.

“Are you studying?” a tentative voice would ask.

“Nope,” I’d reply, grinning as I closed my book. “Today, at school, Gramps, he’s our geography teacher . . .” and I’d make myself start rattling off another funny story.

“Yō-chan, put these glasses on,” Setchan said one night, after she and Sis had come to my room and forced me to give one performance after another.

“Why?”

“Never mind why, just do it. Take Sis’s glasses.”

They were always ordering me about in this brusque manner. So the clown did as he was told and put on the glasses. The second I did so the two sisters burst out laughing.

“It’s him! It’s Lloyd! He looks just like him!”

Harold Lloyd, a foreign movie star known for his comedies, was very popular in Japan at the time.

I stood up, one hand raised.

“Ladies and gentleman,” I began, “I would like to take this opportunity to tell all my fans in Japan . . .” This made them laugh all the harder and from then on I made sure to go to the theater whenever they screened a Lloyd film so I could secretly study his mannerisms and expressions.

Another time, I was lying in bed reading a book one autumn evening when Sis came flying into my room like a bird and threw herself onto my bed, collapsing in a fit of tears.

“Oh, Yō-chan, you’ll save me, won’t you? Of course you will! We should leave this wretched house—just the two of us. Oh, save me! Save me!”

She went on and on like this, raving and weeping in turn. This wasn’t the first time I’d been exposed to a woman in such a state, so I wasn’t terribly surprised at the violence of her words. On the contrary, I found her trite, empty theatrics rather tedious, and, slipping out from under my blankets, I walked over to my desk, peeled a persimmon, and handed her a slice. She sat up at this, sniffing and hiccoughing as she ate, and said, “Do you have any good books? Give me one.”

I took down a copy of Sōseki’s I Am a Cat and passed it to her.

“Thanks for the persimmon,” she said with an embarrassed smile and walked out of the room. She wasn’t the only woman who confused me. All women did. Trying to figure out what was going through their minds as they led their lives was more complicated, more troublesome, and more unsettling than trying to discern the thoughts of an earthworm. All I knew, as experience had taught me from a very young age, was that when a woman suddenly burst out crying like that, the best thing to do was give her something sweet. She’d start to feel better once she ate.

Sometimes the younger sister, Setchan, would even bring her friends to my room. As usual, I’d entertain one and all equally, but once they went home she invariably started criticizing them. You’d better watch out for that one, she’s no good, she’d proclaim. In that case why go to all the trouble of bringing her up here? Thanks to Setchan, almost all of my visitors were women.

However, Takeichi’s prediction, that women would “fall for me,” had not yet been realized. I was still nothing more than northeastern Japan’s Harold Lloyd. It would be several years yet before Takeichi’s ignorant flattery came vividly to life, revealing itself as an ominous, disturbing foretelling.

Takeichi proffered one other, magnificent gift.

“Look! It’s a monster!” He exclaimed when he came to my room, proudly showing me a color print, the frontispiece of some book.

What’s this, I thought. Years later I became convinced that it was in this precise instant that the path I later stumbled down was determined. I recognized the picture. It was merely Van Gogh’s famous self-portrait. French impressionists were all the rage at the time, and, as art appreciation classes typically started off with these kinds of paintings, even middle school children in small country towns like mine could recognize works by Van Gogh, Cezanne, Renoir, and the rest. In my case, I’d seen many Van Gogh prints and been struck by his unique touch and his bright, vibrant colors, yet not once had it occurred to me to think of them as paintings of monsters.

“Well then, how about this one? Is this a monster, too?” I pulled a collection of Modigliani’s paintings down from my bookshelf and showed Takeichi his famous portrait of a nude, her skin like burnt copper.

“Whoa!” Takeichi exclaimed, his eyes wide and round. “It looks like one of the horses of hell!”

“So it is a monster, then.”

“I want to draw those kinds of monster pictures, too.”

Contrary to what you might expect, just as timid and easily frightened people long all the more for a raging storm to grow stronger still, those who live in utter terror of human beings develop a psychological need to see, clearly and with their own two eyes, ever more frightening and terrible monsters but, alas, these artists, so wounded by that monster called humanity, are so terrorized that, in the end, they believe in visions, and monsters appear vividly before their eyes under the merciless glare of nature’s noonday sun. What’s more, they don’t attempt clowning deceptions, they try to depict things precisely as they see them, resolutely drawing “monsters,” just as Takeichi said. Here, I thought, are my future comrades, growing so flushed with excitement that hot tears trickled down my cheeks.

“I’ll paint them, too. I’ll paint monsters. I’ll paint the horses of hell,” I told Takeichi, my voice inexplicably dropping to a faint whisper.

Ever since elementary school I’d enjoyed both looking at pictures and painting my own. Yet my paintings never received as much attention as my written compositions. Since I placed no faith whatsoever in the language of human beings, my compositions were nothing more than a simple form of clowning. Throughout elementary and middle school they sent my teachers into paroxysms of laughter. But they meant nothing to me. It was only in my paintings (cartoons are a different story) that I struggled to express something in my own way, immature though it may have been. The model sketches from textbooks bored me, and the teacher’s drawings were execrable, so I was left to my own devices, haphazardly cobbling together random styles of painting in an attempt to discover one for myself. By the time I started middle school I’d acquired a complete oil painting set, but though I tried to emulate the touch of the impressionists, my paintings always ended up looking flat and blank, the figures like paper dolls. I was at a loss. Thanks to Takeichi, however, I realized my approach had been completely wrong. In my naiveté and ignorance I’d taken things I thought were beautiful and tried to replicate that beauty in my paintings. True masters, however, took the most unremarkable objects and, through their own interpretation, created something beautiful. Or they took the ugliest objects and, through their unabashed fascination, imbued them with the joy of expression, even as the sight of them made their stomachs turn. In short, the true master is not swayed in the slightest by the expectations of others. It was Takeichi who bestowed this secret, this primitive treatise upon me, and, little by little, away from the eyes of my female visitors, I set myself to the task of composing self-portraits.

So dark and gloomy were these paintings that even I shrank from them. Yet, I told myself encouragingly, this is my true self, the one I so assiduously conceal in the depths of my heart. I smile cheerfully on the surface and make others laugh, but in truth mine is a melancholy soul. There was no point in denying it. Even so, I never showed my paintings to anyone other than Takeichi. I was afraid that people might see through my clowning and glimpse the misery it concealed, and I didn’t want to be forced to be on my guard all the time. And I feared they might not realize that the paintings were an expression of my true self but rather see them as some new extension of my clowning and treat them as a hilarious joke. That would be far too much to bear, so I concealed my paintings in the deepest corner of my closet as soon as I finished them.

I also kept my “monster technique” secret at school. In art classes I continued to paint as before, with a mediocre touch, drawing beautiful things beautifully.

Takeichi was the only person I’d felt comfortable sharing my vulnerable, sensitive nature with, so I didn’t worry about showing him my self-portraits. He praised them extravagantly, and when I had drawn two or three more monster paintings, he bestowed his second foretelling on me.

“You’ll be a famous artist someday.”

With these two predictions branded onto my forehead by poor, simple Takeichi—that girls would fall for me and that I’d someday become a famous artist—I soon made my way to Tokyo.

I’d rather have gone to art school, but Father had long since decided to send me to higher school with the aim of making me a government official. As usual, I was incapable of uttering a word of protest when this decision was handed down, and, without giving it much thought, I did as I was bid. I was told to give the entrance exam a try a year earlier than usual, and—being thoroughly sick of my school of sea and cherry blossoms—I passed the exam for a Tokyo higher school in my fourth year and so skipped my fifth year. I lived in a dormitory at first but was repulsed by its filth and brutality. There was no room for clowning in such a place, so, persuading a doctor to write a letter diagnosing me with pulmonary tuberculosis, I left the dormitory and moved into my father’s Tokyo villa in Sakuragi. I could never live in a communal environment. Whenever I heard people going on about the “sincerity and enthusiasm of youth” or the “pride of youth” and that kind of thing I couldn’t suppress a shudder. That kind of talk, that kind of “school spirit” was utterly alien to me. Classroom and dormitory alike seemed to me a midden heap of twisted sexual desire where my near-perfect clowning was of no avail.

When the Diet wasn’t sitting Father only spent a week or two each month in Tokyo, and while he was away there were only three of us in the large house—me and the elderly couple who looked after the place—so I was able to skip classes now and then. Yet I never felt any desire to go out and see the sights of Tokyo (even now it seems I will end my days without ever having seen the Meiji Shrine or the bronze statue of Kusunoki Masahige or having visited the graves of the forty-seven samurai at Sengaku Temple) and instead spent the whole day at home reading and painting. When Father was in Tokyo I rushed off to class early each morning, but I sometimes stopped at Yasuda Shintarō’s Western-style painting studio in the Sendagi district of Hongō instead, spending three or four hours at a time practicing my sketching. Ever since I’d escaped from the dormitory, even when I did show up to class I felt strangely distant from my classmates, as though I were just an auditing student. Perhaps this was a result of my own biases, but it became painfully obvious to me, and I grew increasingly reluctant to attend classes. Throughout my entire time at elementary, middle, and higher schools I never managed to understand what they meant by “school spirit.” I never even bothered to learn any of my school songs.

Not long after I began frequenting the Yasuda studio an art student introduced me to the world of liquor, cigarettes, whores, pawnshops, and Marxism. An odd combination, to be sure, but it’s true.

His name was Horiki Masao. Born in an older part of Tokyo, he was six years older than me and a graduate of a private fine arts academy. Since he didn’t have an atelier at home, he visited the studio so he could continue his study of Western art.

“Hey, lend me five yen, will ya?”

I’d seen him around but we’d never spoken. Flustered, I thrust out a five-yen note.

“Excellent! You’re a good kid. Let’s have a drink—my treat.”

Incapable of refusing, I let myself be dragged to a café district near the studio. That was the beginning of our acquaintance.

“Y’know, I’ve had my eye on you. For a while now. That! That shy smile, right there! That’s the look of someone with the potential to be a real artist. To our new friendship, then—cheers! Hey Kinu, what do you make of this one? He’s a pretty one, don’t you think? Don’t go falling for him, though. Since he started coming to the studio I’m only the second prettiest boy and more’s the pity.”

Horiki had a sallow complexion with sharp, chiseled features, and, unusual for an art student, he wore a suit, favored somber neckties, and parted his pomaded hair straight down the middle.

Unaccustomed to such places, I was in a constant state of terror. I kept crossing and uncrossing my arms, and, indeed, all I could manage was that shy smile. But after two or three glasses of beer, strangely, I began to experience a feeling of lightness, not unlike liberation.

“I wanted to go to art school but . . .”

“No, it’s a bore. Boring! School is boring. Our teacher is nature herself! The pathos of nature!”

I didn’t pay the slightest attention to his words. I thought he was a bit of an idiot, and no doubt his paintings would be terrible too. For all that, though, he might be a useful companion when it came to having fun. In short, for the very first time in my life, I’d met a real, live city scoundrel. Though we looked different—insofar as we were both cut off from the workings of this world of human beings, inasmuch as we were both confused— we were the same. The essential difference separating us was that, unlike me, his clowning was wholly unconscious and he was completely ignorant of its tragic nature.

We were just having fun. He was just someone to go out and have a good time with, I told myself. I scorned him and was even ashamed of our friendship sometimes as we walked about town together. Yet, in the end, I was destroyed even by the likes of him.

In the beginning, however, I thought him a fine fellow indeed. So fine a fellow one hardly saw his like, and, terrified of people though I was, even I was put off my guard as I found myself thinking I had discovered the perfect guide to Tokyo. To be honest, left to my own devices, I was even terrified of the conductors when I set foot on a train. I yearned to see a Kabuki play but was frightened of the young, female ushers who lined either side of the red carpet leading up the theater steps. At restaurants I was scared of the busboys, lurking silently behind me, waiting to clear my plate. And when it came time to pay the bill—oh, how I fumbled. I grew dizzy when it came time to hand over the money. My head spun, the world went dark, and I thought I was going half mad. Not out of parsimony, you see, but because I was so nervous, so embarrassed, so anxious and terrified. Far from trying to haggle the price down, not only would I often forget to take my change, it was so bad that I often even forgot to take the thing I had just purchased. It was utterly impossible for me to go walking about Tokyo on my own. That was the real reason I spent whole days lazing about at home.

When Horiki and I went out, I just handed him my wallet and let him do all of the haggling. He was quite adept at having fun. He could extract the greatest amount of pleasure from the smallest amount of money. We eschewed one-yen taxis, relying instead on his familiarity with the complex network of trains, buses, steamers, and every other cheap means of transport to get us to our destination in the shortest possible time. On the way home after a long night at the brothels he knew which inn to stop at for a bath, boiled tofu, and a quick drink—though cheap, it felt almost luxurious. He equipped me with a practical education. He extolled the virtues of yakitori and beef bowls as cheap and nutritious. He avowed that there was nothing better for getting drunk fast than an electric brandy cocktail. And when it came time to pay the reckoning, he never once gave me cause for anxiety.

Horiki’s true value, however, lay in the fact that he never paid any attention to his listener’s thoughts or feelings. He just went on and on, spouting his “pathos,” with never a break in his banal chatter (perhaps that is the definition of “passion”—the ability to ignore the opinions of one’s listener). When I was with Horiki there was never any danger that, exhausted from walking, we might lapse into one of those awkward silences. Whenever I was around others I was constantly on my guard in case one of those terrifying silences should suddenly appear. Though taciturn by nature, I felt obliged to press on with my clowning, desperately, as though some grand victory or terrible defeat hung in the balance. That fool Horiki, however, assumed the role of clown for himself without even realizing it, so I hardly ever had to speak at all. It was enough for me to smile from time to time and interject the occasional exclamation.

It didn’t take me long to discover that liquor, cigarettes, and prostitutes were wonderfully effective ways to banish my fear of people, if only temporarily. It got to the point where I began to think that selling all I owned would not be too high a price to pay in order to continue these pursuits.

To me, prostitutes were neither human beings nor women but more like lunatics or idiots, and I could find solace in their embrace. I slept soundly when I was with them. They were so utterly lacking in anything like greed it was almost pitiable. Perhaps sensing a kindred spirit, they displayed a natural, though not oppressive, affection toward me. Theirs was an affection free from calculation, an affection devoid of ulterior motives, the affection you feel for a person you might never meet again. Some nights I actually saw the Madonna’s halo hovering over their heads, those idiots and lunatics.

Yet, while I visited the brothels in search of some meager respite from my terror of humanity—if only for a night—and as I entertained myself with my kindred spirits, I started to undergo an unexpected change. An inauspicious aura began to coalesce about me, eddying and swirling. It was, I suppose, a kind of “gift” that prostitutes bestowed on a favored customer, though not one I had expected to receive. The contours of this gift gradually became visible and grew increasingly distinct so that, when Horiki finally pointed it out to me, I was both astonished and, I must admit, disgusted. To put it in objective though somewhat vulgar terms, the whores had been training me. They had been teaching me how to interact with women. Worse still, being prostitutes, they were relentless when it came to the study of this particular field, and their training had already effected quite a change in me. I’d become quite the adept. Already, it seemed, I’d acquired the scent of a “Don Juan” and women (not just whores) seemed to pick up on it instinctively, converging on me. This lascivious and disreputable air, it seems, was the “gift” they’d granted me, and that gift, more than my pursuit of respite, was starting to attract an uncomfortable amount of attention.

Horiki probably intended the remark as a compliment, at least in part. Yet I couldn’t help but feel something disturbing and oppressive in it. For example, there was the naive, childish letter sent by a woman at a café. There was the general’s daughter of about twenty who lived next door to me in Sakuragi; each morning around the time I left for school, she would be loitering near her gate, wearing makeup, for no apparent reason. There was the time I went to a steakhouse and one of the maids—though I hadn’t so much as said a word to her . . . And when I bought cigarettes at the local tobacconist’s, inside the box she handed me . . . The woman sitting next to me at the Kabuki play . . . The night I got drunk and fell asleep on the train . . . When, completely out of the blue, I received a brooding letter from the daughter of a relative back home . . . Or when a girl—I have no idea who—left a handmade doll for me at my house when I was out. I am extraordinarily passive, so none of these incidents developed into anything more, they were mere fragments, yet it’s difficult to deny that some kind of aura seemed to linger about me, ensnaring women. I’m not joking or boasting of my romantic prowess—it is simply the truth. But that someone like Horiki should point it out to me caused a pain not unlike humiliation, and with that my desire to seek the company of prostitutes cooled markedly.

One day, perhaps thinking to appear fashionably modern (being Horiki, it is difficult to imagine any other reason), Horiki took me to a secret gathering, a kind of communist reading group (I think they called it the “R-S” but my memory is vague). For Horiki, this kind of thing was no doubt nothing more than another stop on his “grand tour of Tokyo.” I was introduced to the “comrades,” forced to buy some pamphlets, and then subjected to a lecture on Marxist economics by the leader of the group, a young man with a profoundly ugly face. I couldn’t help but think that everything they said was nothing more than common sense. It was true enough, but there is more to the human soul than just that. There is also something incomprehensible, something terrifying. Desire is too weak a word for it, as is vanity. Even if we combine Eros and desire it’s still not quite enough. I’m not sure myself what it is, but I am certain that the foundation of human society is not economics. It’s something more, with the uncanny air of a strange and scary folk tale. Living in abject terror of that strange folk tale as I did, I was able to accept theories of materialism as easily as I accepted the fact that water runs downhill, but these theories did not liberate me from my dread of humans, they did not arouse in me a sense of joy or the hopefulness of a man whose eyes have been opened to the newly sprouted, green leaves of spring. Nevertheless, I attended every single meeting of the “R-S” (again, I think that was the name but I may be mistaken). It was all I could do not to burst out laughing at their debates. They were all so tense and grave as they became engrossed in their absurd, obvious attempts to demonstrate the theoretical equivalent of one and one making, in fact, two. I used my clowning to try to make the meetings a bit more relaxed, and, perhaps as a result, the atmosphere did grow a bit less stuffy. I was soon so popular I’d become an indispensable member of the group. These naive people must have taken me for one of their own, a naive youth like them. A happy-go-lucky, clowning “comrade.” If so, they were deceived from start to finish. I was not their comrade. Still, I attended every meeting without fail, entertaining all with my antics.

I went because I liked it. Because I was fond of the people. That is not to say, however, that our intimacy was born out of our mutual devotion to Marxism.

“Illicit.” It aroused a faint thrill in me. Or rather, I found the concept almost comforting. For it was the legitimate parts of the world that terrified me (I sensed in them something infinitely strong). Their workings mystified me, and I couldn’t endure sitting in that freezing, windowless room. Though the outside might be nothing but an ocean of lawlessness I thought it better by far to dive in and swim until I should die.

There is a word: “pariah.” In human society this word is used to indicate those who have failed, the pathetic, the immoral. Ever since I was born, I felt I was a pariah, and whenever I met someone that society had also deemed worthy of being so branded I always felt a deep sense of compassion. So deep was my compassion that I sometimes caught myself in silent admiration of it.

There is another phrase: “guilty conscience.” I’ve lived my whole life plagued by my conscience yet, at the same time, it has been a faithful companion—like a devoted wife standing by me through thick and thin as the two of us frolic in our gloom. There’s also the saying “to have skeletons in one’s closet.” For me, those skeletons appeared the moment I was born, and, instead of disappearing as I grew up, they became stronger and more solid until they weighed so heavily upon me that I suffered the torments of a million different hells each night. Even so (no doubt this will sound very odd), they gradually came to be more familiar to me than my own flesh and blood. Their weight, like the pain of an open wound, was like whispered protestations of love. To such a man as me, the mood of the underground political meetings I attended was thus strangely relaxing and oddly comfortable. In the end, it wasn’t the movement’s goals but its nature that attracted me. The only reason Horiki went was to mock them as a bunch of idiots, and, after the initial introduction, he never returned. Their mission might be to research production, he would say, but mine is to research consumption, and, with that lame jest, he never went back, henceforth inviting me only to participate in his research of consumption. Now that I think back on it, I see there were several different kinds of Marxists. Some were like Horiki, people who became self-proclaimed Marxists in a pique of vain modernity, and then there were those like me who, drawn by the scent of the illicit, merely settled themselves in their midst. Had the true believers among the Marxists ever guessed at our real natures I don’t doubt that their anger would have been as a raging inferno. They would have condemned us as contemptible traitors and expelled us on the spot. Yet neither I nor even Horiki were ever expelled. I, especially, felt more relaxed and was able to behave in a “healthier” manner in that illicit, underground world than I could among the gentlemen of polite society, and it wasn’t long before the others came to see me as a promising young “comrade,” entrusting me with all sorts of tasks, each enshrouded in such an absurd degree of secrecy that it was difficult not to laugh. What’s more, I never refused any task, I accepted all with equanimity, I never got rattled or attracted the suspicion of the “dogs” (that’s what the comrades called the police). I never blundered or did anything that would get me taken in for questioning. Laughingly—and making everyone else laugh—I undertook all kinds of dangerous missions (members of the movement would grow terribly tense, as if they were attempting something of monumental importance. Like in a second-rate detective novel, they used such extreme caution in the execution of tasks so insignificant I could not help but feel a bit bewildered by it all. Nevertheless, when it came to making my errands sound perilous, they spared no effort), or so they called them, without flaw or mishap. At the time, the prospect of being arrested as a party member and imprisoned, even if it was for life, didn’t trouble me in the slightest. Compared to the terror I felt toward “real life” in human society and the hellish torments of my nightly insomnia, I sometimes thought that life in prison might be an improvement.

Though Father and I lived in the same house, between his visitors and his going out it wasn’t unusual for us to go three or four days without seeing one another. Still, his was a formidable, terrifying presence and I contemplated moving out—perhaps to some sort of boarding house—but even as I tried to muster up the courage to discuss it, the old caretaker informed me that Father was planning to sell off the house.

Father’s term of office was coming to an end and, no doubt having his own reasons for it, he’d decided not to stand for re-election. He’d drawn up plans to add a new wing to our estate at home as a retreat for his retirement and, not having any remaining ties to Tokyo, he must’ve thought it wasteful to maintain an entire house, complete with servants, for the sake of a mere student (Father’s mind, like the minds of everyone else in human society, was a mystery to me). So the house soon passed into the hands of another, and I moved into a gloomy room in a boarding house called “The Hermitage” in the nearby Hongō district, where I immediately found myself struggling to make ends meet.

Before, I’d been receiving a monthly allowance from Father, and, even if I spent it all in two or three days, there were always cigarettes, liquor, cheese, fruit, and so on to be had around the house. When it came to things like stationery, books, and clothes I could go to any of the local shops and put them on my father’s account. If Horiki and I went out for noodles or a tempura rice bowl, I had only to go to one of the restaurants my father patronized. I could leave without paying and nobody said a word.

Now, suddenly living on my own at the boarding house, I had to make do with the allowance alone. I was at a complete loss. Naturally, my money vanished in two or three days. I was horrified, and, growing so wretched that I thought I might go mad, I sent telegram after telegram to Father, to my brothers and my sisters in turn, begging them to send money, saying I would explain in a letter to follow (the circumstances I explained in those letters were, each and every one, mere empty clowning. I thought that if I was going to ask for something I should at least try to make them laugh). Under Horiki’s tutelage I diligently commuted to and from the pawnshops yet, even so, I was forever short of funds.

In the end, I simply didn’t possess the ability to make it on my own, alone in a boarding house without any connections to help me. I was too frightened to simply stay at home. I would be overcome by the fear that a complete stranger might burst in at any moment and attack me, so, as though dodging a blow, I fled into the city, helping out in the movement or drinking at cheap bars with Horiki. I’d all but abandoned my studies and my painting and, in November of my second year of school, I became embroiled in a love suicide with an older, married woman, and my life changed forever.

I skipped all my classes and never studied for any of my subjects, but I seemed to have an odd knack for exams so, one way or another, I was able to maintain the deception with my parents. However, unbeknownst to me, the school had contacted my parents directly, telling them that I would soon surpass the limit for absenteeism. Soon, at Father’s direction, my eldest brother started sending me long letters full of stern warnings. Yet, what really troubled me—far more than school—was my lack of funds and the fact that my work for the movement had gotten so demanding I could no longer treat it as a joke. I’d been promoted to the head of the Marxist Student Corps for the Central District or something like that. In any case, I was in charge of Hongō, Koishikawa, Shitaya, Kanda, and all the surrounding areas. People started talking about an armed uprising, so I bought a small pocketknife (thinking back on it, it was such a flimsy thing I doubt it would’ve served to sharpen a pencil) and took to carrying it about in the pocket of my raincoat as I ran about town making “contacts.” All I wanted to do was get drunk and sleep like the dead, but I didn’t have any money. And the “P” (that was our code word for the party. Or at least I think it was—I may be mistaken) kept sending me out on mission after mission, never giving me enough time to catch my breath. Given my delicate health it was highly unlikely I’d be able to keep it up for much longer. I’d only started in the movement because I was attracted to the “illicit,” so I couldn’t help feeling annoyed when it began to occupy so much of my time. Privately, I came to the conclusion they’d picked the wrong person for the job and should give it to one of their true believers instead. So I ran away. As you might expect, that didn’t make me feel very good, and I resolved to die.

At the time, there were three women who were particularly fond of me. One was the boarding-house owner’s daughter. After I got home at night, bone-tired from my work for the movement, heading straight to bed without even bothering to eat, she would invariably come knocking at my door saying, “I’m sorry but my brother and sister are making so much noise downstairs that I can’t concentrate on this letter.” And with that she’d settle herself at my desk to write for an hour or more.

It wouldn’t have been so bad if I could have just ignored her and gone to sleep but it was obvious she wanted me to talk to her, and, as usual, this sparked my passive need to please. Worn out as I was, I wasn’t interested in exchanging so much as a single word with her, yet, even so, I gathered up my remaining energy and, rolling over onto my stomach, lit a cigarette, saying, “I hear there’s a man who heats his bath with the love letters he gets.”

“That’s horrid! Talking about yourself, I suppose?”

“I did warm up some milk once.”

“My, my, what an honor. Drink up, then.”

I just wanted her to hurry up and leave. The whole pretense of the letter was a joke. I was certain she was just scribbling nonsense.

“Show me,” I said, though I’d sooner die than read it. What? No! No, you mustn’t, she protested with obvious delight. It was so terribly pathetic that any interest I might’ve had quickly vanished. Then I got the idea of sending her on an errand.

“Hey, I’m really sorry but can you do me a favor? There’s a pharmacy down on the avenue by the streetcars—can you pick up some Carmotine for me? I’m so exhausted I’m burning up, and I’m so tired I can’t even sleep. Would you mind? The money . . .”

“Oh, don’t worry about the money,” she said, jumping happily to her feet. As I knew very well, women are delighted when a man asks them to do something for him, it is never a cause for distress.

The second woman was one of my “comrades” who studied in the humanities at a women’s teacher’s college. Since we were both involved in the movement I saw her every day, whether I wanted to or not. Even after the meetings finished she would follow me around for hours on end and was always buying me all sorts of presents.

“You can think of me as your elder sister.”

Though this crude affectation made me shudder I could only reply, “Of course I will,” forcing my face into a faint, melancholy smile. I mustn’t make her angry, I thought, frightened. I had to distract her somehow. I became so focused on placating this ugly, disagreeable woman that I soon found myself entertaining her. I tried to make her laugh with my jokes, and when she bought me presents (they were always in the worst possible taste, and I gave most of them away to people like the old man running the yakitori stall) I forced myself to feign delight. One summer night when she simply wouldn’t leave me alone, I led her into a dark alley and kissed her in the hope it would make her go home. Instead, she grew wild with excitement, and, overcome by a crude madness, hailed a taxi to take us to one of the tiny offices the movement rented secretly, where we raised quite the racket until dawn. I smiled wryly as I wondered just what kind of elder sister she thought herself to be.

Along with the girl at my boarding house, I had no choice but to see this “comrade” every day, and, unlike the other women I’d known, there was no way to avoid them. Before long my usual anxiety took over, and I was running myself ragged in my attempts to keep the both of them happy. I felt trapped, unable to move so much as a finger.

Around the same time one of the waitresses at a large Ginza café did me an unexpected favor. Though I’d only met her the one time, I couldn’t dispel my sense of obligation, so, again I found myself all but paralyzed with worry and imagined fears. I’d learned by then to affect sufficient impudence that I no longer needed Horiki to guide me about town. I could take the train on my own, go to Kabuki plays, and even walk into cafés, dressed though I was in cheap, threadbare clothes. On the inside, of course, I was the same as I’d always been, and the suspicion, terror, and anxiety I felt toward the violence and confidence of human beings was undiminished. Only on the surface had I slowly reached the point where I could greet people with a straight face. Well, no, that’s not precisely true. I invariably employed the wry grin of a defeated clown, but, regardless, though my greetings and small talk might be hopelessly confused, I’d nevertheless managed to cultivate a “talent” for it. Was it thanks to my work with the movement? Or was it women? Or liquor? The main reason I was starting to acquire these new skills, I suspect, is that I was broke. This induced in me a state of constant terror no matter where I was, and I thought the sense of oppression might ease somewhat if I immersed myself in the jostling crowd of drunks, waitresses, and busboys typical of big cafés. So it was that, with ten yen in my pocket, I went alone to a Ginza café and, grinning at the waitress, said, “I’ve only got ten yen, so don’t expect much.”

“Don’t worry.”

She spoke with a faint Kansai accent. And, oddly, her simple words soothed my jangling nerves. No, not because I didn’t have to worry about money; it was because I got the sense that I didn’t have to worry about being with her.

I drank. I felt relaxed around her, and, not feeling compelled to play the clown, I let my true nature show through, drinking in gloomy, taciturn silence.

“Would you like any of these?” she asked, laying a variety of dishes out on the table. I just shook my head.

“Just liquor? I’ll join you, then.”

It was a cold, autumn night. At Tsuneko’s request (I think that’s what she called herself but my memory has faded so I can’t be sure. That says a lot about the kind of person I am. I even forget the name of the person I tried to commit suicide with), I went to a sushi stall in one of the alleys of Ginza and, eating truly terrible sushi (though I can’t recall her name, the sushi—or rather, how bad it was—remains firmly fixed in my memory. I remember the old man running the stand had a crew cut and a face like a Japanese rat snake. He made a show of flailing about as he made the sushi, pretending he actually knew what he was doing. I can see all of this as clearly as if it were right before me. Years later and more than a few times I have caught myself looking at a face that seems oddly familiar before realizing, with a wry smile, that it looks like that old man from the sushi stand. Though the woman’s name and, by now, even her face have faded from my mind, the fact that I can still recall that old man’s face so clearly I could draw it from memory shows how bad the sushi was and how cold and miserable it made me feel. In any case, though I’ve been taken to supposedly famous sushi restaurants, I’ve never enjoyed sushi. The pieces are too big. Why couldn’t they just make them smaller? Why not just make them thumb-sized?), I waited for her to finish her shift.

She lived in a rented room over a carpenter’s workshop in Honjo. I made no effort to conceal my gloomy nature as I sat in her room, drinking tea, one hand pressed to my cheek, as though I had a terrible toothache. Oddly, rather than being repelled, she seemed drawn to this attitude of mine. She too seemed utterly alone. A cold, early winter wind blew about her, with only dead leaves whirling crazily about her.

As we lay there she told me she was two years older than me, from Hiroshima . . . I have a husband, he was a barber back in Hiroshima but we ran off, came to Tokyo last spring, he never bothered with a proper job after that, he got arrested for fraud, he’s in prison now, I visit him every day, I bring him all sorts of gifts, starting tomorrow I’m not going back. On and on she went, telling me the story of her life. I’m not sure why but I always get bored when women start telling me about their lives. Maybe it’s because they aren’t very good storytellers—they emphasize all the wrong parts—but it all goes in one ear and out the other.

Forlorn.